- Home

- Mary Oppen

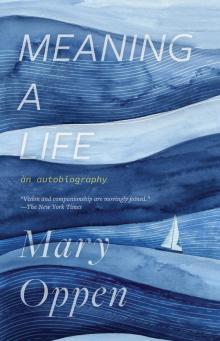

Meaning a Life

Meaning a Life Read online

Meaning

a

Life

An Autobiography

To George, whose life and mine are intertwined

—

Copyright © 1978, 2020 by Linda Oppen

Introduction copyright © 2020 by Jeffrey Yang

Compilation copyright © 2020 by New Directions Publishing

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors of Ironwood, Montemora, and Occurrence, in which sections of this book originally appeared. Further acknowledgments can be found in “A note on the text.”

An excerpt from the introduction with color plates of Mary Oppen’s art was first published in Poetry magazine (February 2020).

Manufactured in the United States of America

First published as a New Directions Paperbook (NDP1477) in 2020

Book design by Eileen Bellamy

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Oppen, Mary, 1908-1990, author. | Yang, Jeffrey, writer of introduction.

Title: Meaning a life : an autobiography / Mary Oppen ; introduction by Jeffrey Yang.

Description: New York : New Directions Books, 2020. | Series: A New Directions book

Identifiers: LCCN 2019055163 | ISBN 9780811229470 (paperback) | ISBN 9780811229487 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Oppen, Mary, 1908-1990. | Oppen, George. | Authors’ spouses—United States—Biography. | Poets, American—20th century—Biography.

Classification: LCC PS3529.P55 Z46 2020 | DDC 811/.52 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019055163

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

ndbooks.com

Contents

Introduction by Jeffrey Yang

A Note on the Text

Meaning a Life: An Autobiography

1908–1917 A Beginning

1917–1925 My Brothers’ Wanderings

1926–1927 Love & Escape

1928–1929 First Travels

1929–1932 France

1933–1937 New York City

1938–1941 Transition

1942–1945 Wartime

1946–1958 California and Exile

So Near

Other Writings

Re: Maine

Nassau + My Trip to Visit Andy

Declaration of Independence

After a Conversation with G.

“Does she think she is a legend?”

On a Dark Night (Saint John of the Cross)

It Is a Life

"deer run wild in"

"Love for another has shaken and"

"our boat makes a way for us"

"I come as a guest"

Mother and Daughter and the Sea

Conversation

Muse

"Is there a woman who knows her own way"

Landmarks

Cover

Introduction

—

The words do not illuminate the poem;

the poem illuminates the words.

—St. John of the Cross

(translated by Mary Oppen)

—

Some books we can read over and over again through the years with renewed delight. Our initial encounter with such a book feels like our first experience with a place we love, or like the first sight of shore or sea—that particular, that vast. Our emotions swirl with promise, hope, jubilation in a miraculous moment of recognition that enlarges our world. How lucky we are to have found this book! How impossible it is now to imagine our life without it! I think of this special-collection library that grows as we grow as our autobiographical canon—resistant to trends, conditioned by intuition and whim, and open to any language or genre.

Mary Oppen’s Meaning a Life: An Autobiography merged into my autobiographical canon through her husband, George Oppen. I was working for New Directions on a posthumous selection of his poems, edited by Robert Creeley, who asked if I could write a chronology of the poet’s life to run in the book. I was a fledgling editorial assistant, the “first stop on the whipping post” of our office, and the request came as a bit of a surprise. High on the challenge, I dove into the chronology with zeal and, after wrestling with it for a few weeks, sent a draft off to Creeley for his approval. Without comment, the Black Mountain master gallantly nixed it. It would be better, he decided, to have someone else do it. Still, all was not lost, as my research had led me to Mary’s book, a copy of which was nearly impossible to track down at the time.

Meaning a Life was originally published in June 1978 by Black Sparrow Press—a California-based literary house built from the ground floor of Charles Bukowski and up through the contemporary American avant-garde— together with George Oppen’s last book of poems, Primitive, which came out earlier that spring. George was already suffering the symptoms of what would later be diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease and, as Mary told an interviewer a few years after his death in 1984, “He couldn’t get [Primitive] ready for the publishers. And he finally said, ‘If you can do this, please do it.’ He said, ‘I can’t do it.’ So I had to put them together and get the typescripts presentable, and probably lots of things he’d have done differently.” Her autobiography opens with the dedication “To George, whose life and mine are intertwined”—an echo of George’s dedication in his Collected Poems of 1975 “For Mary / whose words in this book are entangled / inextricably among my own”—with the entirety of his “Anniversary Poem” as epigraph, one line of the poem questioning, “How shall we say how this happened, these stories, our stories.” What objectively appears to be a rare, celebratory occurrence—the simultaneous publication of a couple’s new books from the same press, both praised later that year in the same review by Michael Heller in The New York Times—with the Oppens feels both ordinary (the common light) and fated (the shining rays of a binary star).

Mary Oppen was born in the kitchen of her parents’ frontier home in Kalispell, Montana, on November 28, 1908, and died on May 14, 1990, in Alta Bates Hospital in Berkeley, California. Meaning a Life was her first book; she turned seventy the year it was published. As she tells the story, she found poetry at the same time she and George found each other. She was eighteen when she met him in a poetry class at Corvallis State Agricultural College (now Oregon State University). On their first date George picked her up in his roommate’s Model T Ford and they stayed out all night, “in the bright / Incredible light” of the moon, as George describes it in his poem “The Forms of Love.” They “sat and talked, made love, and talked until morning . . . talked as I had never talked before, an outpouring,” as Mary describes it in Meaning a Life. She returned to her dorm the next morning and was expelled (George was suspended) for breaking the curfew. She left school, George followed her, and they decided to flee family to make a life of their own, “complete, a mated pair, with the strength of our intelligences, our passions and our sensibilities multiplied by living our lives together,” and with a shared vision of “conversation, ideas, poetry, peers.” They were eighteen! Armed with Conrad Aiken’s anthology Modern American Poets and writing, both soon getting poems published in the same Texas newspaper, for which they ea

ch received a check for $25. Then, almost as soon as she had begun, Mary stopped writing. While hitchhiking to New York, they made it as far as Dallas before she got sick, had an abortion, didn’t recover, and returned to George’s father’s home in San Francisco. She talks about writing and not writing in her autobiography:

The time and the urge to write did not come again to me until I was working on translations of St. John of the Cross in 1971 or 1972. I have quite often translated poems I wanted to read from the original French or Spanish. The St. John translation was so poor in every version I could find that I began to make what I called “transpositions.” From that I began to write again; my readings in the prophets brought me back to a search for my father, who had read Sirach, Ezekiel, the Psalms, the Song of Songs and other parts of the Bible to me. It was as though pent-up emotions were waiting to be released—I wasn’t aware of all I remembered until I tapped at the door and memories came flooding in. Apparently nothing is forgotten, but all is waiting to be called forth; I think I have reached a safe age from which to release these memories which have troubled me over the years. Perhaps they would not have been released for the asking when I was younger.

In an unpublished piece dated December 4, 1975, she shares a little more: “I started to write with the rise of the women’s movement . . . without the women’s movement my writing would not have been respected, in the first instance, enough to break through the male writing world. . . . I have chosen to write at the time culturally prepared for me. . . . I am happy to be writing, very pleased with the loss of shyness that took almost sixty-seven years to accomplish.”

More publicly known is that George Oppen, too, stopped writing from 1935 to 1958, a choice initially connected to what he witnessed as the “catastrophe of human lives” in 1930s America. After spending a summer in Mexico, where the Oppens had witnessed a poor country undergoing a dramatic transformation through socialization, “from colonialism and ‘peonage’ into equality and nationhood,” Mary says about their return to New York: “The city had an air of disaster; the unemployed were the refugees who had exhausted their resources and did not know where to turn.” They also “did not find honesty or sincerity in the so-called arts of the left”—with Mary’s exception of Bertolt Brecht and certain Soviet films—and instead joined the Communist Party and Workers Alliance in Brooklyn, organizing and demonstrating and participating in sit-ins in the Philippine, Puerto Rican, Syrian-Lebanese immigrant neighborhood of Borough Hall, mediating between the relief bureau and poor Southerners in Bedford-Stuyvesant, going to party training school in Utica, and there organizing union meetings and talking with industrial workers and farmers. The stories and observations Mary shares about those difficult times give a poignant account of the daily challenges grassroots activists faced in Depression-era America. Though shocked by the announcement of the Stalin-Hitler pact in 1939, they remained active party members through the war. Writing to a friend in 1959, George pointed to another reason for not writing: the birth of their daughter, Linda, in 1940—“Julian: there were only some fifteen years that political loyalties prevented me from writing poetry. After that I had to wait for Linda to grow up.”

Words arrived before the life. Meaning a life lived close to the roots, meaning into words, words a measure of the life, in pursuit of meaning, meaning through seeing, listening, thinking, “to find a way of life in which the poetry we felt within us could come out of our lives.” The first two chapters of Mary Oppen’s book—a beautifully discursive and concise prelude—lead up to the moment of their romance. She recalls her childhood in isolated Kalispell, a place “where children and Indians were the only natives,” a homesteading railroad and lumber town in the Rocky Mountains settled by families from the east, Germans and Scandinavians, three Chinese laborers, Protestants, Lutherans, and Catholics. Vivid memories of growing up in the woods with three older brothers; Papa, a postmaster and later a Ford dealer, then an investor in Chinese imports; and Mama, of Norman Catholic ancestry who worked multiple jobs and ran the house: “Rhythms from ancient times still held everywhere in the weekly order of household work.” The seasons pass with the day’s milk delivered by horse and wagon, smudge-pot summers at Flathead Lake, getting a pair of soft deerskin moccasins made at the coulée Indian encampment, preserved eggs checked against a light box in the basement, a lit candle gently placed in a snow-dome, watching the Aurora Borealis with Papa before bedtime, the Chinook wind of spring and the sound of snowmelt.

After a short stretch in Seattle, her family moved to Grants Pass, Oregon, when she was twelve, a one-street town settled by prospectors, farmers, and lumberjacks, though if you were black, she notes, you weren’t permitted to stay overnight. It was the start of Prohibition, which as Oppen reflects, “incited lawlessness and added an air of secrecy and license, an air of drunkenness, to sex.” She talks about teenage courtship being “the flushed and struggling girl finding no safe, satisfying or honorable outcome.” It was the dawn of the Nineteenth Amendment. An impoverished, filthy old couple with a derelict farm lived on their block, along with two families of Osage Indians who were oil-rich, dignified, “their beauty almost burned the town.” Oppen read everything “from Maeterlinck to Sax Rohmer” in the town’s “pitiful” library and planned her escape from a place that “held for me the greatest danger I could conceive: to be trapped in a meaningless life with birth and death in a biological repetition, without serious thought or a search for life with more meaning.” At fifteen her father died from cancer and she was suddenly plunged into a loneliness neither wilderness nor sex could alleviate. She worked and saved money for college.

What is essential, what is formative in a life recollected? Is it the nonessential that gives memory its unconscious form and awaits whatever remembrance warrants? Mary Oppen’s book is subtitled “An Autobiography,” the sign signifying the life at the heart of its literary enterprise, as the etymology goes: autos (self), bios (life), graphein (to write, to record). In both the East and West the practice traces back to the fourth century, with Tao Qian and Saint Augustine, both impulses coming out of disparate traditions of written biographies. The poet Robert Southey is mistakenly credited with coining the English term in 1809, long after and during the erasure of America’s oral autobiographers, the written stories of the indigenous not materializing until the 1830s in a complicated collaborative process that usually involved at least one native informant-translator and a white anthropologist-writer (Paul Radin’s Crashing Thunder: The Autobiography of an American Indian comes to mind as a particularly fascinating example). Anna Robeson Burr’s landmark The Autobiography: A Critical and Comparative Study appeared in 1909, the same year William Dean Howells, the “Dean of American Letters,” called autobiography in his Harper’s Monthly column “a new form of literature” and “the most democratic province in the republic of letters.” Not an original opinion though still a mark of its rising popularity. Indeed, autobiography seemed made for America. A handful of sources are often pointed to for ballpark numbers: Richard G. Lillard’s American Life in Autobiography (1956) lists 440 titles published in the first half of the twentieth century; Louis Kaplan’s A Bibliography of American Autobiographies (1961) lists 6,377 titles published before 1945; Mary Louise Briscoe’s American Autobiography, 1945–1980: A Bibliography (1982) adds 5,008 titles to Kaplan’s list; Patricia K. Addis’s Through a Woman’s I: An Annotated Bibliography of American Women’s Autobiographical Writings, 1946–1976 (1983) lists 2,217 titles; Russell C. Brignano’s Black Americans in Autobiography (1984) lists 710 titles.* From early colonial chronicles, settlers’ narratives, captivity narratives, spiritual-conversion narratives, slave narratives, suffragist narratives, and on with the rise of literacy and work-play diversification, through “descent with modification,” as Darwin described evolution, the autobiography in America has become game for any hook, vocation, or identity, from supertramp to robber baron, open to all and anyone who can write down their memories and tell their

own story, publication self-guaranteed, a dream of the song of myself woven by everyone themselves.

And like any dream it comes with risks, which is perhaps why, even today, the genre is still treated like an unwanted guest in the glass house of belles lettres. For one, it is easily prone to the “calculated distortion and tactical offhandedness” that Theroux accuses Kipling of in Something of Myself. I think of Gulliver’s reply to the Shropshire Captain who urged him to put his story “in Paper” upon his return to England: “My answer was that I thought we were already overstocked with books of travel; that nothing could now pass which was not extraordinary; wherein I doubted some authors less consulted truth than their own vanity, or interest, or the diversion of ignorant readers.” For “books of travel” read “autobiographies,” a genre that has always existed on the outskirts of literature, written, or read, more as an afterthought to the “real” creative work at hand. A sentiment Ezra Pound must have shared when he wrote in a letter to the New Directions publisher James Laughlin, “When a man writes his meeemoires that’s a sign that he’s finished.” Still, at age thirty-five Pound did write a short one in the guise of a book of travel, or “Harzreise” as he called it (an allusion to Heinrich Heine’s account of his journey to the Harz Mountains), titled Indiscretions: Or, Une Revue de Deux Mondes, a humorously coded, racially cringeworthy romp through his family annals; he also wrote/compiled a gem of one based on his friendship with the artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, subtitled “A Memoir.” Pound’s daughter, Mary de Rachewiltz, also wrote one, Ezra Pound, Father and Teacher: Discretions, that came out in 1971, the year before her father died, in which she interspersed lines of The Cantos throughout as luminous evidence of the lived life embedded in the lifelong poem.

As Basil Bunting says in his masterwork Briggflatts, “A strong song tows / us.” Even devoted fans of his delicately structured poem might have forgotten its original subtitle, “An Autobiography.” Bunting’s poetic aspirations are expressed in the poem itself as reverence for the Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti, who “condensed so much music into so few bars / with never a crabbed turn or congested cadence, / never a boast or a see-here.” Oppen is likewise studious of condensation in her prose, her understated, carefully attentive sentences always testing the truth of her experiences without overreaching. She relates their chosen life together—the life that fills the rest of her book beginning with “Love & Escape”—in this way:

Meaning a Life

Meaning a Life